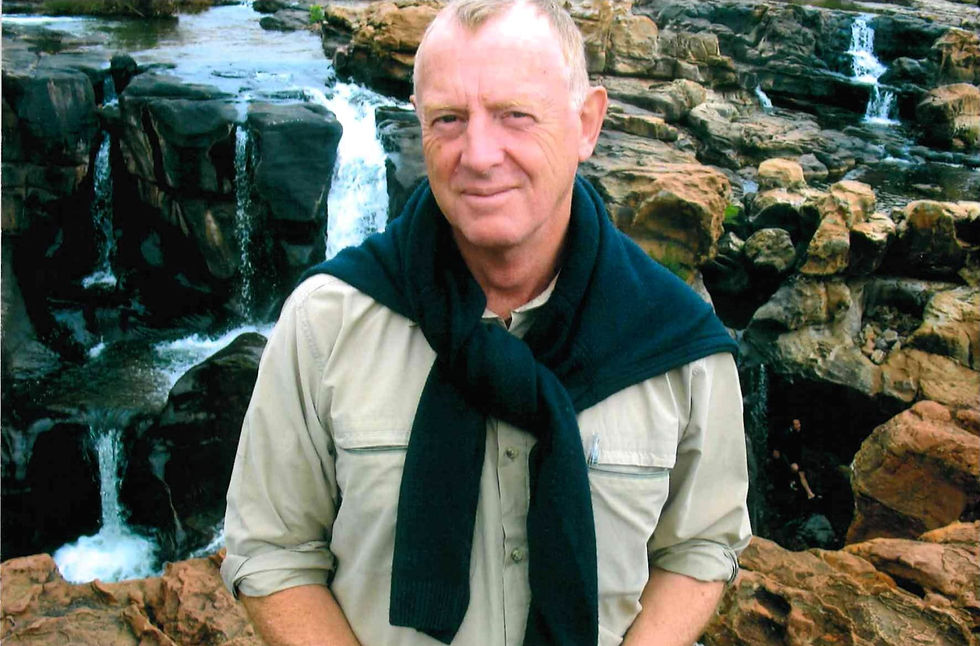

Fr John's African Diary... from 1969!

- Missio Scotland

- Nov 7, 2023

- 3 min read

Fr John Doran 1969 was quite a year! The Americans put a man on the moon, Pope Paul VI visited Uganda—and I saw him—and the most recent conflict in the North of Ireland took hold. I was 21 and I wrote a diary of my 10-week visit to Africa, which I have just reopened after 54 years!

After two years in the Mill Hill House of Studies in the Netherlands, seven of us were chosen to visit the ‘missions.’ Four of us went to Cameroon and three of us went to Uganda. My two Dutch classmates were assigned to parishes and I was assigned to a leper hospital on the north shore of Lake Victoria. I learnt more in those 10 weeks than in any other 10 weeks in my life. It was all so new and exciting!

Uganda—the ‘pearl of Africa’ as Winston Churchill once called it was, at that time, peaceful, newly independent, with a highly-motivated civil service, police force (unarmed) and local government. Poverty was real and made sudden appearances, such as when I walked into a government hospital to find 700 patients, but only 400 beds and five doctors.

People were wary of soldiers. The Minister of Defence was one Idi Amin. The president at the time was Milton Obote. The staff of the hospital were like the cast of a film. The stars were the lepers themselves—some 400 patients—who were coping with this debilitating and socially isolating disease. Plenty more were outpatients.

The backbone of the hospital was the community of religious, the Franciscan Missionary Sisters of Africa, known as the ‘Kevinites’ after Mother Kevin, their Irish founder. Two members of this order still reside in Renfrew! As far as I remember, there were four Irishwomen, one Englishwoman and two African women from the Teso people.

The chaplain was a Dutch Mill Hill Father, Fr Harry Steegmans. He had built his house, spoke fluent Luganda and had a wealth of experience. Mr Goes—pronounces goose—was 73 and our resident hunter from the ‘Out of Africa’ days. He went out alone to shoot hippos or elephants to provide food for the patients and staff. I ate hippo once. I mentioned to Sr Rosalia—the superior—that when the wind shifted suddenly one day, Mr Goes would probably die, trampled by an elephant. She smiled and said: “He’d probably be happy to die that way!” I was shocked, but now I think I know what she meant.

Doctor Blenska was a mature Polish lady, who was a specialist in leprosy and a World War II survivor. Her physiotherapist was also a Polish woman. A visiting doctor was a Dutch Franciscan priest from Ethiopia. He had been in the Resistance and had escaped from the SS prison in Rotterdam. World War II cast a long shadow. The man who ran the hospital administration, Mr Bayer, had been quartermaster on the pocket battleship Admiral Scheer. They’d sunk 20 merchant ships and one armed merchantman off the coast of Africa.

A young Bavarian ran the farm, while a Dutch couple ran the workshops and technical support. Karen, another German, was the matron with Sr Aelred. A Dutch teacher, Marianne led the education team.

My diary was full of information. For example, on July 10, 1969, I noted that I shaved off my beard after a year. Also it reminded me that I had an anti-malaria overdose. Africa in the 1960s was wilder. Hippos bathed in the Nile at sunset. I once saw a lioness prowling beside a main road in daylight.

As soon as I stepped off the plane in Africa I arrived into a hot, scented night under the moonlight. The Mill Hill Fathers and Brothers were welcoming and men to be looked up to. The people were hospitality itself. The first African priests had already been ordained. We foresaw the day when they would replace the white missionaries. Most of us didn’t realise that they would also become foreign missionaries to other lands, even to Scotland and England. The Bishop of Jinja took us west, to the border with Congo, to a Game Park. I got to meet an interview a leading ‘witch doctor’ about leprosy!

Many years later I returned to Africa. One evening, sitting in front of a fire on the high plains of South Africa, a friend and parishioner said: “You are falling in love with Africa. You will never leave.” He said he could see it in my eyes. At the time I laughed, but as the years passed, I began to realise what he meant, but missionaries go where they are sent. Part of my heart is still in Africa, but my mission is now here, with the people of Scotland.

Comments